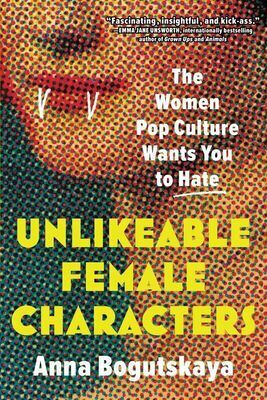

Screenwriters are often told that female characters have to be “relatable,” a term considered less offensive than “likable” and yet somehow an adjective rarely, if ever, applied to male characters. But ever since the earliest days of movies, audiences have loved to watch fiery, outspoken, courageous, and wicked female characters, from the Wicked Witch of the West in “The Wizard of Oz” to Margo Channing in “All About Eve,” from Cruella de Vil in “101 Dalmatians,” and Alex Forrest in “Fatal Attraction” to Shiv in “Succession.” Anna Bogutskaya’s new book, Unlikeable Female Characters: the Women Pop Culture Wants You to Hate (forthcoming May 9, 2023), is deeply researched, with fascinating behind-the-scenes details and insightful analysis. It is also wildly entertaining, categorizing characters as bitches, sluts, witches, mean girls, angry women, trainwrecks, crazy women, psychos, and shrews. Bogutskaya says those are “adjectives that have been used to describe women just to avoid saying that they’re good at something.” In an interview, she talked about her very funny footnotes, two Oscar-nominated roles played by women but written for men, and her favorite Disney villain.

I’m going to say something I don’t think I’ve ever said before: I particularly enjoyed your footnotes.

Thank you so much for appreciating that. It’s not me trying to be David Foster Wallace or anything like that. I think it’s a way of breaking up this sometimes-weighty pop culture analysis with a bit of humor.

I was surprised to find that two of the most awarded films of 2022, “Everything Everywhere All At Once” and “TÁR,” were originally written with male lead characters. So, what does that tell us about how screenwriters think about female characters?

I wish I had time to include both of those films in the book. I finished writing it before I saw either one. But this happened with “Alien,” with Sigourney Weaver’s character, Ripley, written as a male character. It is the same thing. The implication is that they’re written as a character with agency, with thoughts, with ambitions, with a personality that wasn’t beholden to certain invisible rules. And once they are gender-flipped, Michelle Yeoh’s character, Cate Blanchett’s character, as well as Ripley are some of the most incredibly nuanced, beautifully portrayed, thorny characters of the last year in movies. And they were originally written for men. What does that tell us? It’s both very silly and very revealing.

Not to disparage those roles at all! They were two of my favorite films of last year. And Lydia in “TÁR” in particular, I think you could write a whole book just about her and all the elements that she contains. But it is just one of the myriad of things that goes to show that there are these invisible shackles that exist around most fictional women, that they have to abide by something.

One area where there’s been a lot of equality is Disney villains. There are about an equal number of female and male Disney villains. And of course, the most memorable of all Disney villains, I think it’s fair to say, is Cruella de Vil. Do you have a favorite?

My personal favorite Disney villain is Ursula. But Cruella I find fascinating because even Glenn Close, who portrayed her in the first live-action adaptation—having played many unlikeable characters on the spectrum of manipulative, tortured, insane—she said in an interview that Cruella de Vil was the only one who was completely and utterly unredeemable, which tells you something.

The Disney villains in particular, the most exaggerated ones—Cruella, Ursula—they all want something. They have this ambition or this goal or this desire, usually completely self-serving, be that creating a coat out of Dalmatian puppies or be that being the mistress of all the oceans and the seas. It’s the ambition and the hunger for something that is deemed to not be for them.

You spend a lot of time in the book on one of the most unlikeable female characters in movie history: Amy Dunne in “Gone Girl.” One of the things that interest me about her is her monologue about the pressure she feels to be “the cool girl.”

I find the whole debate around “Gone Girl” to be deeply interesting. And part of my thinking in selecting the characters to dive deeper into in the book is the cultural backlash that was created around them. And with Amy Dunne, there have been so many articles, think pieces, essays, and discussions around whether “Gone Girl” as a story is a feminist text and Amy, in particular as a character, is a feminist character.

I think it can be both and neither. So, I think “Gone Girl” is a feminist text. Amy Dunne, as a character, is not. She hates women, and she reserves a particular kind of bile and spite towards other women, both in the book and in the film. As much as she despises the shackles that she has put upon herself in order to be the cool girl, the game girl, and bend herself and her abilities and her intellect into something that would be acceptable for men and for the man that she wants, she also takes it out on other women. So, I don’t think she’s interested in female liberation or in women supporting each other.

I’m not going to diagnose her—I’m not a licensed psychotherapist. But people have called her a sociopath, a psychopath. In my book, I called that trope the psycho, because that’s the overarching pop culture term that we usually use. She’s one of the most interesting ones because she’s completely designed the world so she is fundamentally correct in every single sense, and everyone else is lesser than her—men or women. It actually doesn’t really matter that much to her. She’s annoyed at people that she considers to be lesser than her, that managed to outsmart her or fool her, which is why, when she absolutely goes off and creates this whole scheme against her husband, Nick, it’s not because she hates him or because she hates the fact that she’s been the cool girl for so long and is so frustrated by that—it’s because he fooled her and her delusion about herself is so high that she cannot fathom that someone could outsmart her. That’s why I think she’s such a fascinating character. Because every single person that I’ve spoken to about Amy Dunne has a completely different read on her.

That chameleonic character who can be vicious in a completely different way for different people in the audience and different readers is fascinating because she’s tapping into fears around womanhood in so many different capacities, from the idea that women lie about being assaulted, from the way that she manipulates her womanhood, to even the way that she is engineered into looking down on and competing with and absolutely being disinterested in helping or being helped by other women. But she will weaponize her womanhood when it is handy for her, not for anyone else. No one else exists for Amy Dunne.

Glenn Close has said that she was a little surprised that people hated her character in “Fatal Attraction” so much.

Well, I’ve seen and heard a lot of interviews with Glenn Close, especially about her character in “Fatal Attraction,” and I’m not sure I agree with you that I think she was incorrect. It’s in her performance as well. She’s never playing Alex as a simplistic madwoman; she’s playing someone who has issues already at the heart of that character from the very moment we meet her. But the way that she’s reacting, she’s only reacting to information that she’s being given.

The short film that “Fatal Attraction” is based on, the whole point is about the consequences of your actions, and the real villain, the person who’s making informed choices in that regard, is Michael Douglas‘ character. He’s the one who’s got a family. He’s the one who’s married. He’s the one who chooses to have an affair with a coworker and then decides to discard her, completely selfishly. I’m not justifying her reaction, but the reaction of the audience to her, the way that the ending was changed [from having Alex kill herself to having her killed in self-defense], the way the people were screaming, “Kill the bitch!” in the theatre, which has been very documented, shows us the natural sympathies of people.

I think it’s incredibly telling of the culture at the time in which the film was released, the way that that character was received, and how that has subsequently shifted not that much, but a bit, because we are living in an era where there’s a lot of narratives and pop culture around reclaiming people and fictional characters as well. And very recently, and echoed in the book as well, Glenn Close has said that she would love to see a version of that story that’s told from the point of view of Alex. I would love to see that.

I think there’s a layer of empathy that shines through in Glenn’s performance for audiences who perhaps are looking at this film with 10, 20 more years of feminist critique and thought and repositioning films and thinking, Actually, wait, why was she doing this? The question is: why? Why was she driven to this extent, to this kind of reaction to the affair that she has with Michael Douglas’s character?

So, I don’t think she was incorrect in thinking that she has elements that make her sympathetic. I think she’s a really tragic character. That’s the word I would use. She goes to extremes.

Just today, I rewatched “Sunset Boulevard.” Obviously, Norma Desmond is murderous. We start off with the voiceover from her victim. As the movie progressed, and maybe because I’m older since I saw it last, I see her, and same with Alex, as such tragic figures where they were fitting themselves into all of these expectations of them—how to be a star, how to be a successful independent woman in the America of the 1980s. And then they become so fragile because they’re stretching themselves so thin with all of this that when the time comes with that push, with this one man they’re obsessed with, they go off the rails. And it doesn’t make me hate them as characters. It makes me really feel for them. So, I would agree with Glenn Close. I think Alex is a really sympathetic character.

You covered so many of my favorite movies in the book. And one that I was particularly happy to see because it’s not very well known is “Female” (1933), with Ruth Chatterton as a woman who heads an automobile company and sleeps with the handsome men who work for her. But that character was only possible in the pre-Code era.

Well, there are so many movies that I could mention, but I wanted to specifically bring that one to attention, because sometimes we have this erroneous notion that everything was much worse in the past, and silent Hollywood and old Hollywood female characters were very strict, very conservative, they didn’t have agency, they didn’t have any power. And that’s not true.

Watch those films, especially the pre-Code ones like “Female,” like the Mae West films. Anyone watching Mae West films—“I’m No Angel,” for example—watching now and thinking, “This is outrageous, even by 2023 standards. How is she getting away with this?” And the same with “Female.” You know, you look at Shiv Roy in “Succession” now. It’s because it’s a portrait of corporate ambition, right? Of monetary ambition, of climbing the social and economic ladder. But it seems almost more provocative now that it’s a woman that prioritizes money and financial success over relationships.

I want people who are not necessarily film critics or film nerds to read the book and to see a wider breadth of the sort of films that I’m talking about, not just the really well-known ones, not extreme deep cuts, but rather to see that there was a lot of freedom, and it was clamped down after the Hays Code came into effect. The aftereffects of the production code can still be felt, and we’re just now in the last decade or so climbing out of that.

But as you point out, actresses like Barbara Stanwyck and Bette Davis always played these very complicated characters.

Bette Davis is well documented to have actively gone after roles that are deeply unlikable and no other actress wanted. From the very start in “Of Human Bondage,” nobody wanted that role. She campaigned for it for a couple of years because of the quality of the role.

Back to Shiv. Why do you include her in the book?

She thinks she is morally superior; she thinks she is intellectually superior. But (no spoilers) she gets betrayed in such a brutal way at the end of season three because she could not fathom that anyone could outsmart her. Similar to what I said about Amy Dunne. And for that, I find her really interesting because she’s not just ruthless, she’s not just unlikeable, she is a failure in this world in which she exists and in which she thinks she’s hot stuff. And I love that as a character because it makes her so human and complicated, and so much more than just an Alexis Carrington [from “Dynasty”] who comes in and looks great, and has all the zingers. She knows how to put down her brothers, and walk out of the room looking great and having outsmarted everyone else. But she fails just as much as they do.

You write about the difference between what a Black female character can do and what a white female character can do, and how they can do the same thing and be seen in different ways. What are some examples of that?

There are simply quite a lot more examples of white unlikable female characters than all the other female characters of other races. And I’m specifically thinking about US cinema and television of course. Part of that has to do with the stereotypes of the “angry Black woman,” that there is a certain expectation of Black female characters to be boisterous and angry by default, as opposed to coming from a righteous place or from a place where the character has been affected in some way. And you can see that a lot in exploitation films.

And outside of all the systemic reasons why Black actresses, in particular, were not allowed, just never in consideration for those types of roles, then that goes hand in hand with the stereotypes of the Jezebel as the oversexed woman, of the angry Black woman.

But there are really beautiful and complicated exceptions, like Dorothy Dandridge as “Carmen Jones.” She doesn’t exactly fall neatly into any of the archetypes that I describe precisely because there is such an additional pressure on Dorothy playing that role. Because, just by the sheer nature of her race, you have this added layer of meaning that’s put upon her.

I love the taxonomy of archetypes you included.

I wanted to stick with pop culture characters that are so foundational because they create these archetypes that then become almost these boxes that we can put real-life women into. And where does that come from? It comes from movies. It comes from TV. And this need to classify women either as likable or unlikable serves no purpose aside from just keeping women insecure.

Do you aspire to any of those categories?

Maybe I’m all of them [laughs].