Roger Ebert was a champion of independent films, and he was never more enthusiastic than discovering a new filmmaker with a fresh perspective. That is most evident in his support for Black filmmakers like Spike Lee, Julie Dash, and John Singleton. In honor of Black History Month, here are some of our favorites from his reviews and features.

Ebert was fearless in his aesthetic judgment. He was also fearless about admitting that he was wrong. One of his most insightful reviews is his reconsideration of Charles Burnett’s 1978 film “Killer of Sheep,” which he originally dismissed with what he admitted was “a sentence so wrong-headed it cries out to be corrected” in his Great Movies essay on the film:

“But instead of making a larger statement about his characters, he chooses to show them engaged in a series of daily routines, in the striving and succeeding and failing that make up a life in which, because of poverty, there is little freedom of choice.” Surely, I should have seen that what Burnett chooses to show is, in fact, a larger statement. In this poetic film about a family in Watts, he observes the quiet nobility of lives lived with values but without opportunities. The lives go nowhere, the movie goes nowhere, and in staying where they are they evoke a sense of sadness and loss….What he captures above all in “Killer of Sheep” is the deadening ennui of hot, empty summer days, the dusty passage of time when windows and screen doors stood open, and the way the breathless day crawls past. And he pays attention to the heroic efforts of this man and wife to make a good home for their children. Poverty in the ghetto is not the guns and drugs we see on TV. It is more often like life in this movie: Good, honest, hard-working people trying to get by, keep up their hopes, love their children and get a little sleep.”

“It’s High Tide for a Black New Wave“

From the 1991 Cannes Film Festival, Ebert wrote about the rise of movies from Black filmmakers that made no effort to pander to white audiences:

“As a film critic who had seen virtually every “black film” of the past 20 years, I felt at once I was seeing something new here: A film not only made by blacks, and about blacks, but for blacks. So many of the other black films seemed to be trying to force themselves into white mainstream categories. As a white viewer, I found [Spike] Lee’s approach incomparably more interesting than those tortured “crossover” films that seemed to be translated into an idiom that didn’t belong anywhere.…[Lee] has moved on beyond the ritual charges of racism, beyond the image of wronged and angry black characters, to a new plateau of sophistication on which there is room for good and bad characters of all races, on which racism is seen not as a knee-jerk response to skin color, but as a failure of empathy–a failure of the ability to imagine the other person’s point of view.”

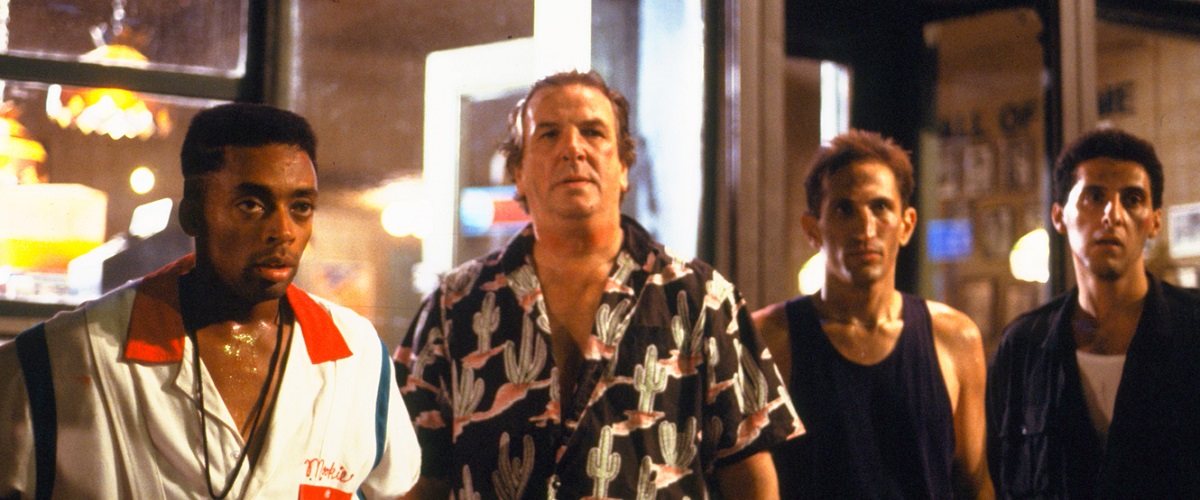

Ebert not only gave Spike Lee’s masterpiece the perfect score of four stars, but he also selected it as one of the “Great Movies” he assembled as his pantheon of undisputed classics. He called it one of the few films that “penetrate one’s soul.”

“Spike Lee was 32 when he made it, assured, confident, in the full joy of his power. He takes this story, which sounds like grim social realism, and tells it with music, humor, color and exuberant invention. A lot of it is just plain fun.”

“Do the Right Thing” was later introduced by Lee at Ebertfest, and Chaz Ebert, along with Barry Jenkins, presented Lee with the Ebert Director Award at the Toronto Film Festival in 2023.

Ebert was also a big fan of Lee’s film of the Tony Award-winning musical “Passing Strange.” Though it was a filmed theatrical musical performance, not a traditional cinematic narrative, he wrote, “This is a superb ensemble, conveying that joy actors feel when they know they’re good in good material. This is not a traditional feature, but it’s one of Spike Lee’s best films.”

“The Inkwell” and “Straight Out of Brooklyn”

Ebert was very enthusiastic about these two films directed by Matty Rich, made on a budget too small even to be considered micro. “Straight Out of Brooklyn,” also written by Rich, was filmed with a $900 camcorder, starting when he was just 17, and released when he was 19. Ebert appreciated its initiative and authenticity. “The edges are rough and the ending is simply a slogan printed on the screen. But the truth is there, and echoes after the film is over.” “The Inkwell” was released when Rich was 22. “Rich is still learning as a filmmaker, and he needs to tell his actors to dial down. But he knows how to tell a story. And he knows how to get big laughs, too.”

It’s rare to find a straightforward movie romance with Black characters. Ebert’s review of the Sidney Poitier/Abby Lincoln film, “For Love of Ivy” came out so long ago (1968) the actors were referred to as Negro. He liked the movie, which, for the record, was directed by a white man, but his review is about how to review a movie about Black characters that has minimal, if any, commentary on the overall Black experience.

“Because the two central characters are black, I found myself asking all kinds of ideological questions: Is the movie “honest”? How does it portray the racial situation in America? Does it sell out? Does it deal in stereotypes? Does Poitier play another impossibly noble character?

This is the mental routine movie critics seem to go through whenever a Poitier movie opens. Since Poitier is an authentic superstar (and possibly today’s top box-office draw), all sorts of moralists try to advise him on whether he’s doing his duty, whatever that is. Usually they decide that Poitier movies ignore the racial crisis and paint an unrealistically rosy picture of black-white relations.

I think this criticism misses the point, and may even be a sort of triple-reverse racism.”

Ebert called Julie Dash’s “Daughters of the Dust” “a tone poem of old memories, a family album in which all of the pictures are taken on the same day…. The film doesn’t tell a story in any conventional sense. It tells of feelings. At certain moments we are not sure exactly what is being said or signified, but by the end we understand everything that happened – not in an intellectual way, but in an emotional way.”

Ebert interviewed John Singleton, director of “Boyz N the Hood” when the late director was just 26.

“The main characters are not the smartest ones, I said. They’re all naive. It’s the more ideological people who have given their positions more thought. The skinheads. The black militants. The feminists.

Singleton nodded. This was one late afternoon after a Chicago screening of his film, and we had moved across the street to a Mexican restaurant to talk.

The Fishburne character is fascinating, I said. He’s scrupulously neutral and constitutionally conservative: He tries to be color-blind, values only excellence, believes in hard work and holds the young hero to the same standards. He kind of balances out the black militant student. Is that what you were thinking of?

“Not exactly. He’s kind of conservative, but not militantly conservative. That’s the way I wanted Fish to play him. He believes in not making excuses because of racism, you know, or sex and anything else, and every time Malik comes to him with a complaint, he always refutes it, telling him, `Hey, you can’t blame your problems on that.’ But even he, in the end, has to admit that there’s a system that tries to keep things in check, you know. A certain institutional bias that is slanted against kids like Malik. The professor believes that, to be a good teacher, he can’t allow himself to come too close to his students; they may have problems, they may be victims to some degree, but he can best help them by being the best teacher he can.””

Ebert wrote, “There has been no more assured and powerful film debut this year than “Eve’s Bayou,” the first film by Kasi Lemmons….[It] resonates in the memory. It called me back for a second and third viewing. If it is not nominated for Academy Awards, then the academy is not paying attention. For the viewer, it is a reminder that sometimes films can venture into the realms of poetry and dreams.”

He also praised the “visual precision” of the film, also later presented by the director at Ebertfest.

The legendary Maya Angelou directed “Down in the Delta,” and Ebert respected her unintrusive approach, letting the actors carry the story.

“Angelou’s first-time direction stays out of its own way; she doesn’t call attention to herself with unnecessary visual touches, but focuses on the business at hand. She and Goble are interested in what might happen in a situation like this, not in how they can manipulate the audience with phony crises. When Annie wanders away from the house, for example, it’s handled in the way it might really be handled, instead of being turned into a set piece.”

Ebert interviewed Robert Townsend after the release of “The Five Heartbeats,” a film about a singing group. He recapped the director’s history, his years with “my mother looking for the back of my head” as an extra, his love for classic films from directors like Frank Capra and Alfred Hitchcock, and his low budget satire of the Hollywood treatment of Black performers, “Hollywood Shuffle,” which Ebert described as “a ragged film, no masterpiece, but it had spirit.”

“[Heartbeats is] not simply a showbiz movie, though, I said. There’s a lot of drama about families in it, and about how some of the guys grow up faster than the others, and one wanders off into drugs.

“Yeah. I wanted it to have more body, to go a little bit deeper. A lot of movies don’t have real values anymore. They’re disposable, geared toward one weekend. They just throw a lot of noise and action at you. They don’t care. You look at the shape of the country, and the crime statistics, and then you look at the movies, and a lot of them are catering to that climate of violence, helping to feed it. I just have different values.””

Finally, in this episode of the Siskel & Ebert series, the critics discuss three Spike Lee films, “She’s Gotta Have It,” “School Daze,” and “Do the Right Thing.”